If Leonardo da Vinci were around today, he’d be running this new UCalgary course. Similar to the Renaissance genius who saw art and science as one, Dr. Paivi Miettunen has created the university’s first pilot course on learning anatomy via sculpting.

Two years ago, Miettunen, pediatricrheumatologist at the Alberta Children’s Hospital and assistant professor of pediatric rheumatology at the university, wanted to balance her crazy-busy medical life by taking a sculpting course in Rome. There, the former stained glass artist not only rekindled her passion for art, but realized that the artist’s knowledge of anatomy was superior to hers.

Hence, the MED 440 course Portrait Anatomy in Sculpture was formed, thanks to a generous private donor, the collaboration between the Cumming School of Medicine and the Faculty of Arts, as well as the instruction of a sculptor who studied and taught at the prestigious Florence Academy of Art.

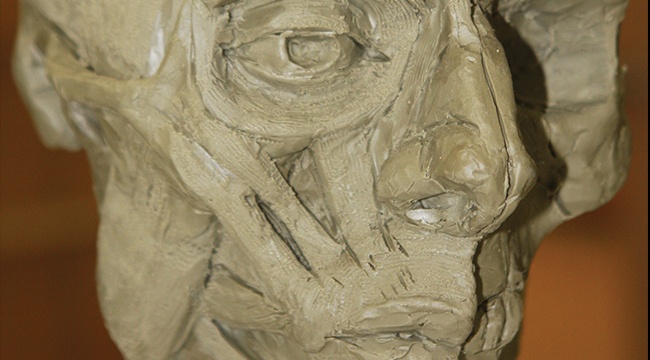

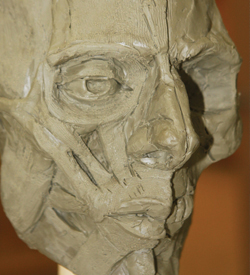

Miettunen brought Alicia Ponzio to teach last semester’s one-week interdisciplinary course that involved building a life-size human skull and the layers of muscles and soft tissue that surround it. “It’s really a method of study that I’m teaching more than trying to teach them fine art,” says Ponzio. “[The students] are learning a new way of memorizing information … and the level of enthusiasm is exciting.”Both Miettunen and Brian Rusted, head of the Department of Art, hope to see the course become a permanent elective in both the medical school and arts curricula. This, in turn, could take the collaboration further by “opening the way to the development of an art history course on medical illustration and an arts criticism course that medical students could use to develop their diagnostic skills,” says Rusted.

Adds Miettunen: “Hands-on sculpting helped train my eye to be more observant ... and made me look at the human form in a different way. “I think, for a physician, it’s incredibly important to be able to read a face … it’s the most expressive part of a human being. [Sculpting] helped me see my patients better and, as a result, helped me interpret illness and wellness better.” U